Reinhard Festag (Managing Director, BigRep), Matthias Katschnig (CTO, HAGE3D), Sven Thate (Managing Director, BigRep), and Thomas Janics (CEO, HAGE3D) at Formnext 2023.

In our quest to offer exceptional Additive Manufacturing technology, and solutions and expand our capabilities, today marks a monumental day in the history of BigRep as we announce the acquisition of HAGE3D. This partnership signals a giant leap toward our vision of becoming a full-solution ecosystem for a range of low to high-temperature applications, offering a powerhouse of innovation and possibilities.

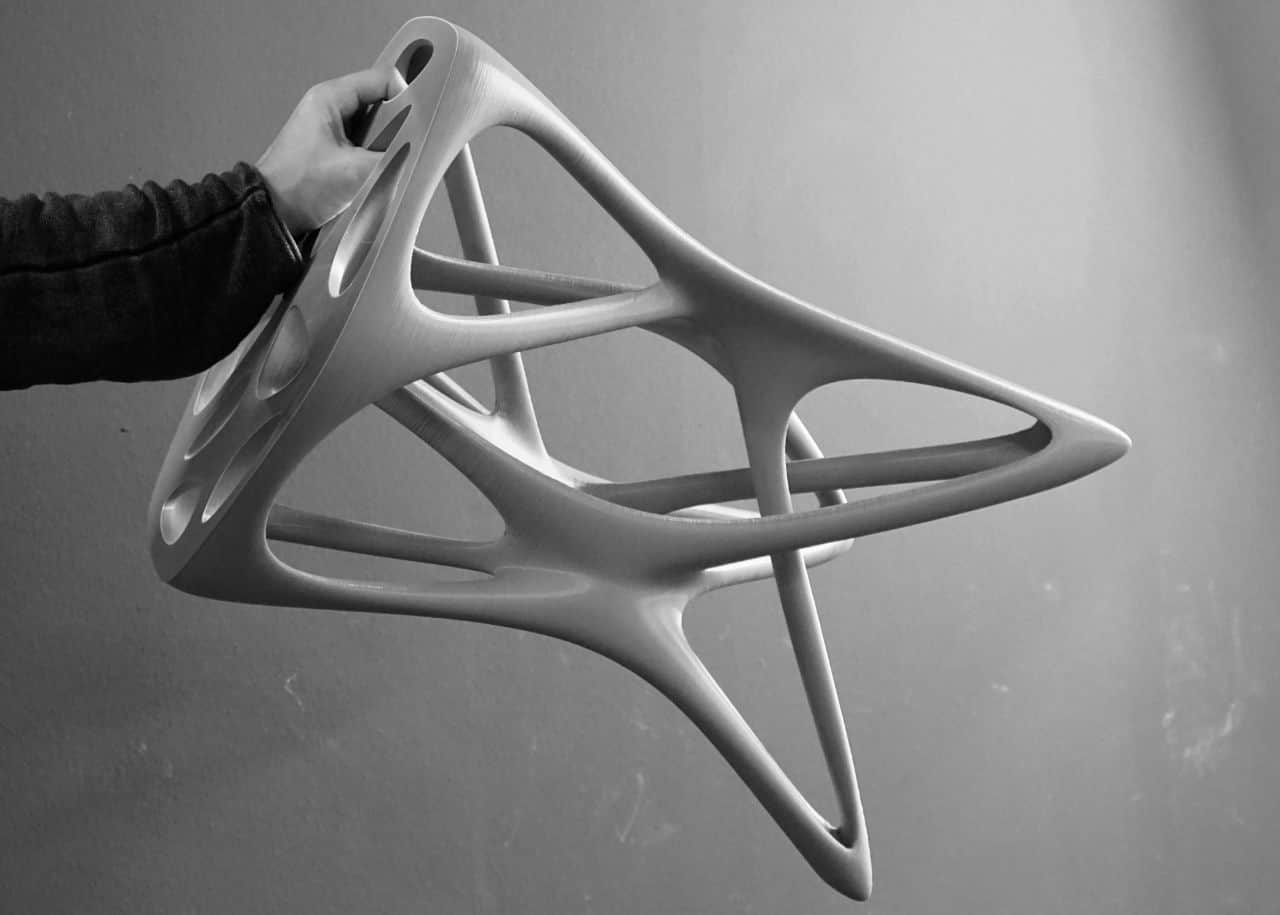

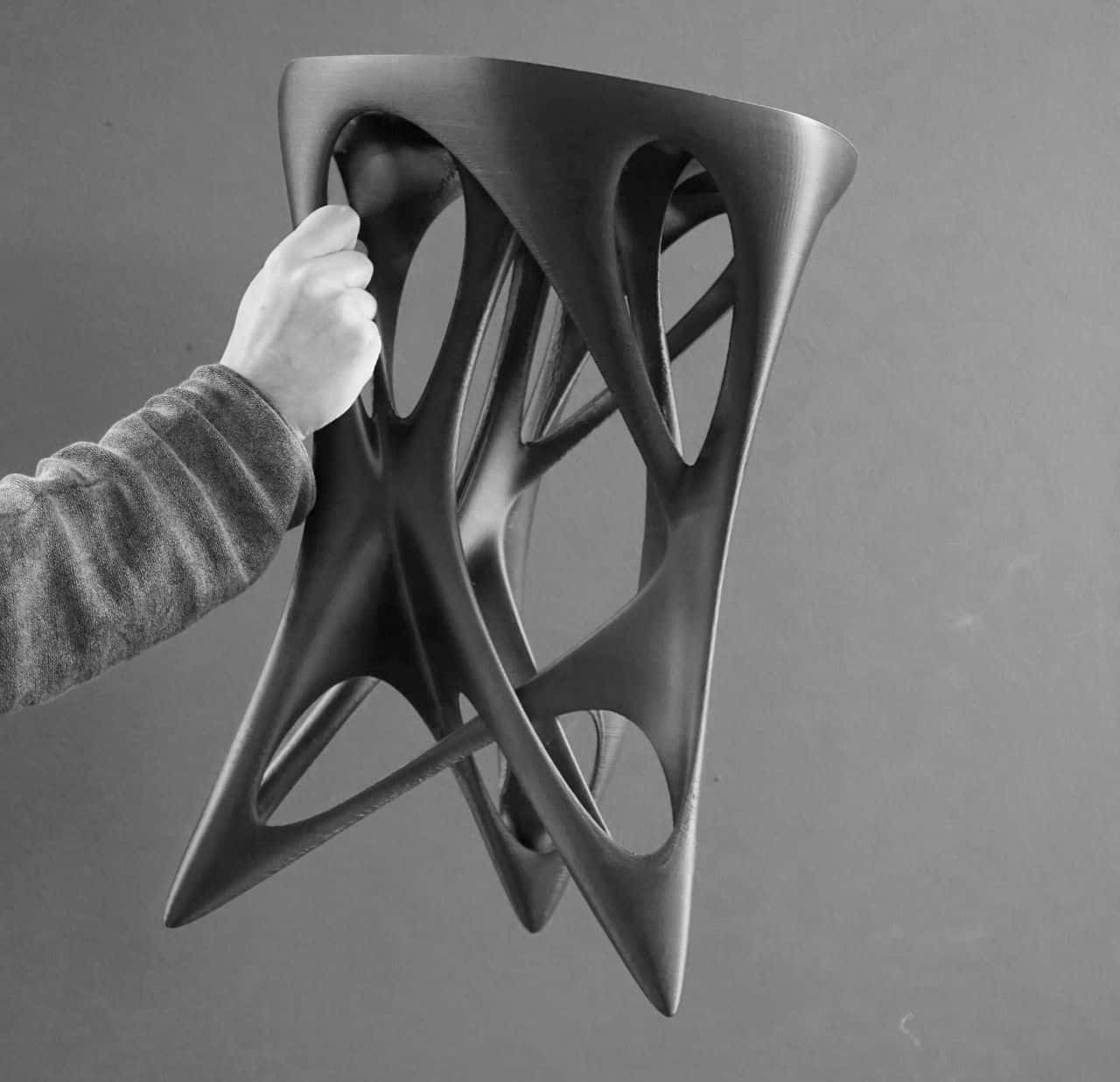

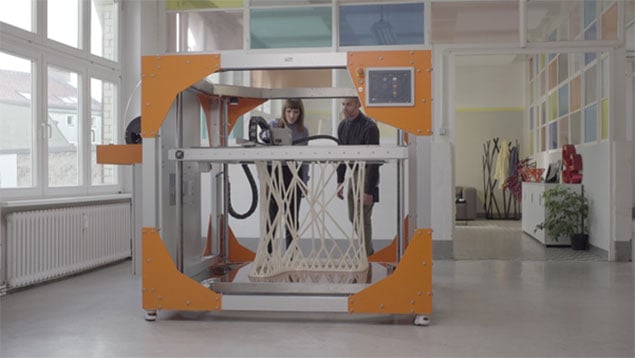

The collaborative path with HAGE3D will unlock new opportunities in the industrial 3D printing landscape. Together, we offer a comprehensive portfolio of industrial 3D printers, featuring up to one cubic meter build volume and the capabilities of a wide range of high-performance, engineering-grade thermoplastic materials in low, mid, and high-temperature build chambers.

Redrawing the AM Landscape

HAGE3D, renowned for its high-temperature 3D printers and open AM platform, will empower BigRep to offer a full spectrum of low-to-high-temperature solutions. The acquisition is built on a foundation of extensive technological synergies, data-driven innovation, exceptional customer experiences, and an ambitious expansion plan, further strengthening BigRep's position in the industry and extending our market reach.

The Acquisition Disrupts Existing Possibilities

Both companies are committed to the development of intelligent FFF technology, making the production of complex, large-format functional parts accessible to manufacturers worldwide.

Dr.‐Ing. Sven Thate, Managing Director of BigRep GmbH, expressed his excitement about the merger, highlighting how it positions BigRep as the AM market continues to grow dynamically. The 3D printing world is driven by megatrends such as digitization and decentralization of manufacturing and BigRep, with the addition of HAGE3D, is well-prepared to capture this opportunity.

Dr.‐Ing. Sven Thate, Managing Director of BigRep GmbH, elaborated:

“For our worldwide customers, this acquisition makes us their local provider of open industrial AM solutions across all temperature levels, unlocking limitless material options. Together, with similar mindsets of customer-centric, data-driven innovation, we plan to form a European leader pushing the limits of what is possible with FFF.”

Thomas Janics, Managing Director of HAGE3D, emphasized the global growth opportunities enabled by HAGE3D's high-temperature FFF platforms expanding BigRep's material portfolio and large-format AM solutions. Complementing its current low‐temperature and energy‐conscious large format AM platforms, this will open a broad spectrum of new applications and markets.

Thomas Janics, Managing Director of HAGE3D, explained:

“With BigRep we have found a perfect partner to accelerate global growth opportunities in the industrial AM sector. While our focus was previously on the German‐speaking markets, we now can provide our products globally through BigRep´s sales network, adding Graz to the map of technology centers next to BigRep’s in Berlin, Boston, Shanghai, and Singapore. It’s a win‐win in R&D, production, and sales. We jointly look forward to an innovative future together.”

Joining Forces for Innovation

With more than 1,000 large-scale 3D printers already in operation across various industrial sectors, BigRep has earned its reputation with its expertise in large-scale Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF). The German-engineered 3D printers empower engineers, designers, and manufacturers, spanning from startups to Fortune 100 corporations, to expedite the transition from prototyping to production, ensuring their products reach the market promptly.

On the other hand, HAGE3D is an advanced engineering company with 40 years of experience in large-format, special-purpose machine building. Their state-of-the-art large-format mid- and high-temperature 3D printing systems are known for their precision and reliability. Fully assembled in Austria using industrial-quality components, these machines perform consistently across a wide range of industries and applications.

By forming an alliance with HAGE3D, BigRep is poised to expedite innovation and redefine manufacturing practices. This integration is underpinned by a fully integrated open AM business model, promising to offer users a replete solution.

As BigRep and HAGE3D come together, we will continue to push the limits of what is possible with FFF technology, accessing a world of opportunities in large-format, open additive manufacturing.

Find out more at https://bigrep.com/press-media/